The Origins of English Financial Markets: Investment and Speculation before the South Sea Bubble is required reading at Pinnacle Digest. Written by Anne Murphy—a former investment banker and derivatives trader in London—the book illuminates the creation of financial products in England’s late 17th century, and in doing so, offers a rare glimpse into the psychology of investors and stockbrokers of the past.

A timeless classic, the Origins of English Financial Markets provides enduring advice that should not be lost on speculators today. Instead of diving into a sector or current event this week, let’s take a look at London’s first stock market boom in the 1690s to see what, if anything, has changed since then. Remember, those that ignore history do so at their own peril…

The Origins of English Financial Markets

The Origins of English Financial Markets derives much of its early knowledge from the ledger of upholsterer-turned-stockbroker Charles Blunt, cousin of the infamous John Blunt—chief architect of the South Sea Bubble. The book essentially explains the beginnings of the environment that gave birth to the South Sea Bubble.

Leading up to that bubble, about 100 new English joint-stock companies came to trade between 1688 and 1695. (source: Scott, Constitution and Finance, vol. I, p. 327.)

With many parallels to the current environment, examples and behaviours from that bygone era still move markets today.

5 Parallels Between Late 17th Century England and Today

Catalyst Event

Every market needs a colossal success story that excites the masses, thereby creating a catalyst for future investment.

Market catalysts usually come in the form of industry changing events, new transformational policies or outlier companies that perform exceedingly well. Whatever the case, the changes or success stories are well-publicized so as to draw in the masses.

Just think of the media hype and returns in the cannabis sector over the past number of years—like a vacuum, the marijuana industry sucked up liquidity from virtually every sector within Canada, some more than others.

For 17th century London, the catalyst was Captain William Phip’s sunken treasure discovery off of the coast of Hispaniola in the West Indies. The year was 1641 and his haul, which consisted mainly of silver, was valued at more than £200,000. Phips was knighted and became the talk of the town for years.

For supporting his expedition, Phips’ key backers were paid a dividend of over £5,000 pounds for every £100 invested. Incredible returns.

Unsurprisingly, it didn’t take long for the actual profits to be distorted, like many market tales we hear about today.

A recovered diary details the talk at the time:

“The Duke of Albermales share came to £50,000, & some privet Gent: who adventured but £100 pounds & little more, to ten thousand.”

source: J. Evelyn, The Diary of John Evelyn, edited by E.S. De Beer, 6 vols.

Much like a great fishing story, these figures were likely grossly overvalued. However, that didn’t stop the people of London from buzzing with the prospect of overnight wealth. Wreck diving was just the beginning. Soon ‘projectors’ or ‘financiers’ began raising capital through joint-stock funding deals of all kinds, ranging from manufacturing and mining enterprises to insurance and bank companies. Stocks of all kinds heated up.

Exclusivity

The key to the beginning of any boom. But beware, by the time everyone else gets in, the moment has already passed.

Wild success stories continued into the late-1600s; but, as was the case with Phips, exclusivity was a constant theme. Though few investors actually reaped the gains, many told the stories.

Founded in 1668, the Hudson’s Bay Company began with just £10,500 in capital. Moreover, it had only 18 shareholders at the time, according to William Scott, author of the Constitution and Finance of English, Scottish and Irish joint-stock companies to 1720.

Anne Murphy explains in The Origins of English Financial Markets that,

“Even the East India Company, which operated with a far larger capital, had only 511 shareholders by 1688.”

Today, every company on the TSX Venture has hundreds and in many cases thousands of shareholders. In comparison, England’s first issuers were exclusively held by a small number of people—a fact that only stirred further interest from the masses. The same principle of exclusivity holds true today. How many of us were invited to participate in the Facebook IPO or top cannabis IPOs?

Far less than those who would participate in the open market after.

Furthermore, and this would become key in setting off the stampede into London’s first stock market and the ensuing South Sea Bubble of 1720:

“The rewards for those few were great, especially during the 1680s.”

Finally, Murphy relays that,

“It was during this period that the East India Company paid dividends of 25 per cent, and in 1689, 50 per cent. The Hudson’s Bay Company also paid a 50 per cent dividend several times during the 1680s.”

The top companies with so few shareholders at this time had more money than they could spend. The idea of issuing new shares was preposterous—why share the wealth or tinker with something that was paying so well?

When something is exclusive, virtually everyone wants in. It’s classic human nature—we want what we can’t have. When it comes to returns and investing, this principle could not be truer. That stated, the individual almost always follows the crowd.

Limited Investment Opportunities

Today we have hundreds of thousands of potential investment opportunities; in the 1690s there were but a few.

When investment opportunities in a hot sector are minimal, an obscene amount of money (relative to the size of the market) can be dominated by just a handful of companies. This creates a boom that, as evidenced by the 2017-2018 rise and fall of the cryptocurrency market, can quickly turn into a bubble.

In 16th century England, The Nine Years’ War (1688–97) between France and most of Europe (including England) obstructed trade at sea. One merchant by the name of Samuel Jeake recorded the following in his diary,

“…& I making but 5 per cent of my money at interest upon mortgages and bonds, upon which I could but barely maintain my family.”

With war grinding trade to a halt, many mercantilists were prevented from making money. Those left with capital were desperate for a return, and thus more than willing to speculate given the limited opportunities.

Innovation

No one likes investing in yesterday’s products. People want to invest in the technologies of tomorrow.

But where do these innovative technologies come from?

Historically speaking, war.

Indeed, nothing spurs innovation like war; from the internet to encryption and canned foods, some of our most innovative and life-changing technologies/products were developed to get an edge on the battlefield.

With The Nine Years’ War (1688-97) upon them and the lives of their fellow countrymen at stake, British inventors were working overtime—inventing everything from ship steering wheels to flintlock muskets.

Although ancient history to us, these novel inventions likely captured the imagination of the masses, thereby nurturing a highly speculative and risk-tolerant mindset. An attitude of “we can make anything we put our minds too.” Essentially, a period of successful innovations can heighten optimism.

Think about the excitement around 5G networks or autonomous vehicles today—investors of the 1690s would have likely felt a similar enthusiasm toward the steam pump, barometers, blood transfusions, pocket watches, the reflecting telescope or pressure cookers (all invented in that century). It was a great period for innovation.

Proof of a surge in human ingenuity can be seen in the doubling of patent activity from the 1680s to the 1690s. J.D. Chambers wrote about the late 17th century growth,

“A more significant measure of expansion was the doubling of the number of patents for invention in the last ten years of the century……an advance which represents “a surge of inventive talent”… which was not to be repeated until after 1760.”

A Brand-New Industry

Five years ago, few understood cryptocurrencies or A.I. Speculators weren’t investing in 5G infrastructure or the next IoT (internet of things) technology. But today, most investors are acutely aware of these technologies, due to the endless possibilities that their industries present.

During 17th century England, all kinds of new industries were being created—the most profound of which was perhaps the life insurance industry.

But life insurance wasn’t the only game in town. For most, they cared about the here and now, and how they could get rich. Big, new, shiny things have a way of attracting speculative capital.

Diminishing Faith in Traditional Safe Havens

While the U.S. dollar remains strong, there is an underlying weakness in many of today’s global currencies due to the excessive money printing that has gone on since the Great Recession of 2008.

The English currency was under serious pressure in the late 17th century. While this topic could challenge its own Weekly Intelligence Letter, the nation’s currency (silver coins) was rapidly eroding in value due to the fact that 10% of the country’s floating currency was made up of forged coins. In an effort to stabilize the English currency, the English government undertook the Great Recoinage of 1696—just two years after the formation of the Bank of England…

The Bank of England began the age of central banking we know today. It was the first bank of its kind created with the sole intent of lending money to the English government to keep it solvent.

On the Bank of England’s website it reads,

“The original Royal Charter of 1694, signed by King William III, explained that the Bank was founded to ‘promote the public Good and Benefit of our People.”

Anne Murphy, author of The Origins of English Financial Markets,has a slightly different view:

She goes on to explain that the establishment of the Bank was a,“symbol of the overthrow of a monarch and the rise of Parliament.”

“For many contemporary observers the Bank of England represented the forming of the ‘moneyed men’ into a cohesive group whose wealth presented a challenge to the existing social elite and whose direct connections to government seemed to give them the power to influence policy decisions.”

Finally,

“It also represented the move away from an agrarian society in which power and stability was vested in land, to a society that gave power to those in possession of intangible and inherently unstable forms of wealth.”

Source: The Origins of English Financial Markets

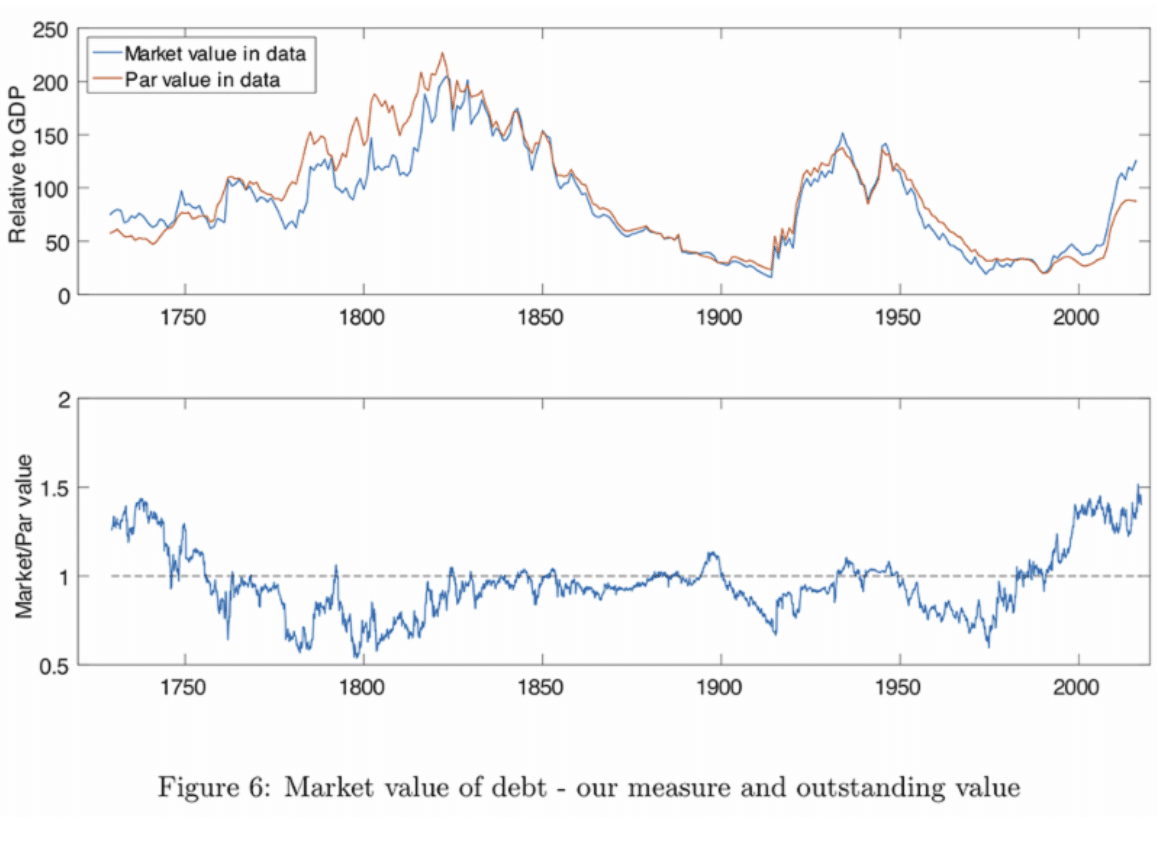

England’s debt has only grown since the formation of its central bank. The White Paper Managing the UK National Debt 1694-2017 by Martin Ellison and Andrew Scott documents as much:

“It is striking that the market value of debt at the end of the sample stands at its highest ratio to par value since our sample begins.”

The market value of debt is shown in the chart below. The U.K., like most of the Western world, is terribly indebted.

Wrapping Up

The power that central banks wield today is phenomenal. But instead of standing in awe of their power, or ignoring the influence they have over money (and thus our lives), it’s important for investors to understand how the debt-based monetary system works. If properly understood, investors can better protect their investments, and also speculate when it is wise to be risk-tolerant or risk-averse.

The Origins of English Financial Markets and London’s first stock market boom are more than just a reminder of our financial system’s history—they provide a masterclass on the conditions necessary for financial booms and bubbles to take hold. One would do well to remember the 5 “parallels” mentioned, given that they still influence the global markets—and by extent, Canada’s small and micro-cap markets—to this day.

All the best with your investments,

PINNACLEDIGEST.COM

If you’re not already a member of our newsletter and you invest in TSX Venture and CSE stocks, what are you waiting for? Subscribe today. Only our best content will land in your inbox.